Woman’s College

Celebrating the excellence of WC

The worst days for America gave it perhaps the most outstanding public college for women.

Woman’s College (WC) was established as the Great Depression entered its third, horrible year. More and more men were becoming unemployed and marriage rates continued to decline, leaving young women urgently seeking ways to sustain themselves. At this campus, many found not only that, but also a pathway to empowerment.

Building on the legacy of the Normal School, the Normal College, and the North Carolina College for Women, WC provided many women across the state affordable access to higher education. They whole-heartedly committed to the College’s motto of “Service,” and did so on their own terms – spurring an extensive impact on education, health care, and administration, across the state.

Harriet Elliott, who would serve in several national roles under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, exerted a major influence over Woman’s College. As a faculty member in the Department of Political Science and History, she introduced into her classroom concepts of responsible freedom, women’s rights, an informed electorate, the democratic way, and what she called the dead weight of uniformity. In 1935, when she became Dean of Women, she carried her ideals up the administrative ladder.

Harriet Elliott, center, with students, 1940.

BUILDING ON THE FOUNDATION

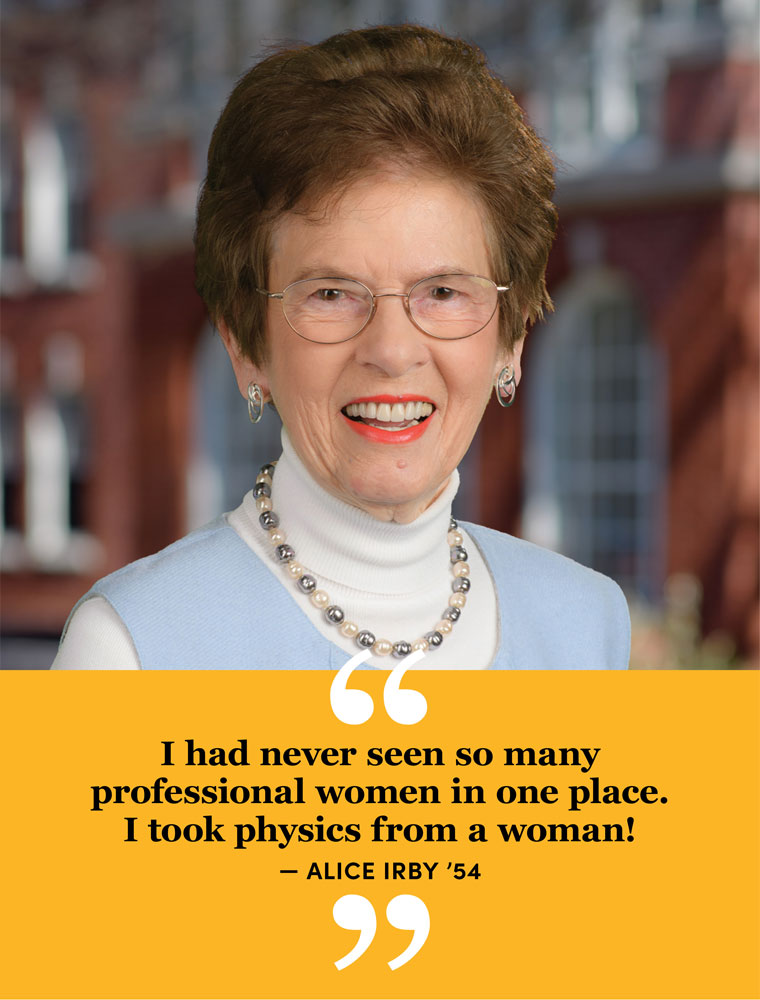

“Harriet Elliott helped make Woman’s College what it is,” said alumna Alice Irby ’54. “And she died just two or three years before I started as a freshman. So that was the foundation and the environment in which I entered WC, and it was life changing.”

Alice arrived in 1950 as a young woman from the rural, eastern part of the state. She had felt the effects of the Great Depression and WWII growing up, and the Korean War then filled the headlines.

But none of that was on her mind as she stood in line in the gymnasium to sign up for classes. WC had a liberal arts core curriculum, which was a feature she relished. All freshmen and sophomores – with the exception of music majors – had to take math, science, English, history, a foreign language, physical education, and health. So she chose her courses accordingly.

Alice was now a part of one of the largest colleges for women in the country. In her freshman year, WC had just opened Jackson Library – a major upgrade from the tight quarters of Carnegie Library. The Home Economics building was being reconfigured, and Walker Avenue was officially closed off as a through street, making it safer for students to travel across campus. Essentially, the heart of the College was under renovation.

“They hadn’t created any sidewalks or landscaped the area, so it was mud,” Alice recollected. “And it kept raining, so we were just slogging in the mud. They laid the sidewalks based on the mud paths we created going to class.”

As an economics major, she spent a lot of time in Jackson Library. The mandatory study hours from 7 to 10 p.m. just weren’t enough for her rigorous academic schedule. Excelling in her work, though, Alice was eventually accepted into the campus’ prestigious honor society, the Golden Chain.

A fierce motivator was the presence of able women surrounding her – and the absence of boys.

“I had never seen so many professional women in one place. I took physics from a woman!” she said emphatically.

And the faculty weren’t just progressive, they were personable, often going beyond the call of duty. When Alice undertook an independent studies program, Dr. Eleanor Craig offered to tutor her in economic theory.

“Can you imagine having your own professional tutor in college, and a professional woman at that?” Alice noted in her memoir that Dr. Craig worked extra hours, without compensation, to assist her. ”What encouragement…having a very able young woman in my field show enough interest in me to give me a foundation for graduate study!”

Making one of the biggest impressions on Alice, though, was Dr. Warren Ashby – a professor in the Department of Philosophy – first as a teacher, then mentor and friend. They had chats in the Soda Shop (in the building now known as the Faculty Center), where students and faculty regularly met. He and his wife, Helen, often invited Alice to their home.

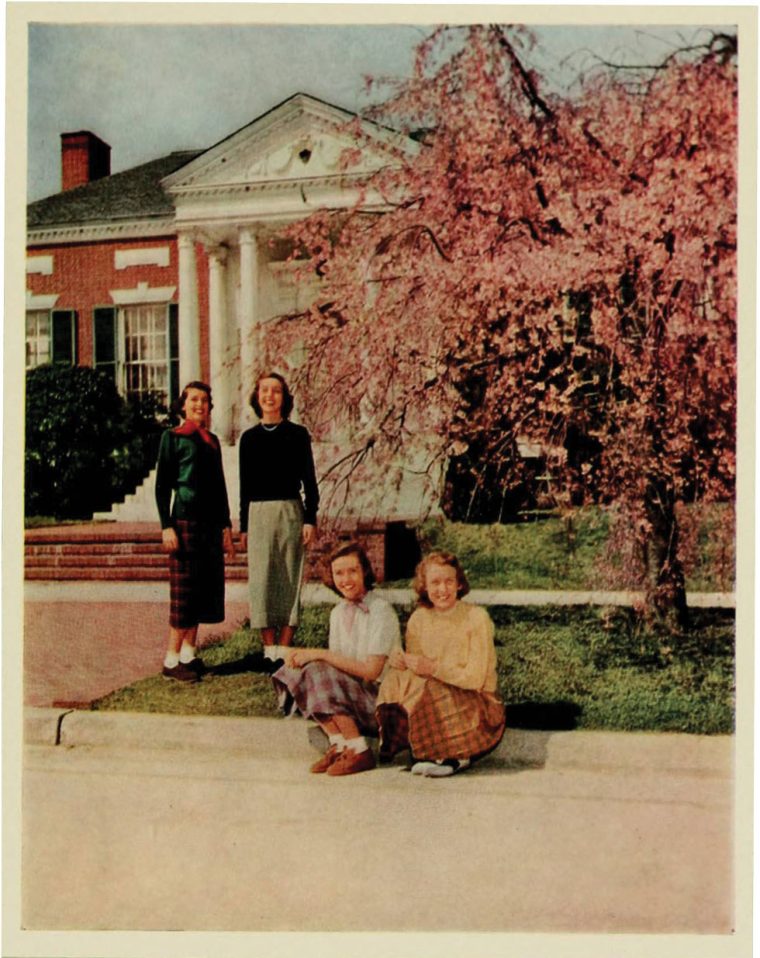

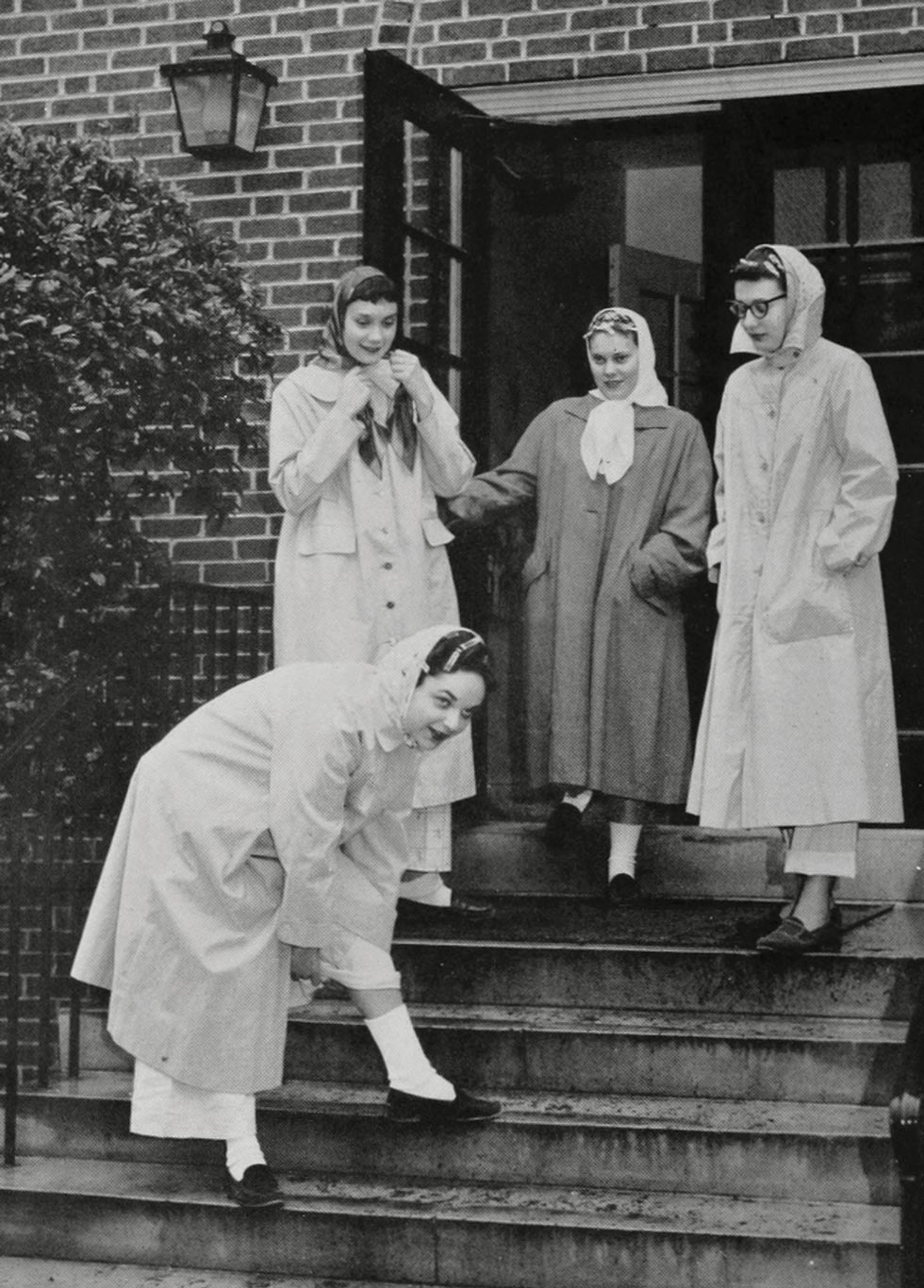

Students in front of the Alumni House, 1952.

“Their home became Grand Central for a lot of us,” said Alice. “I remember sitting on the living room floor of Warren Ashby’s house, watching the McCarthy hearings.”

Senator Joseph R. McCarthy’s pervasive hunt for communists was a sore spot for many WC students, who feared an encroachment on their freedom of speech. In the student newspaper, the hearings were referred to as one of America’s “historically grotesque tragedies.”

Around the same time, the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka ruling was shaking up the nation, officially declaring racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional.

Dorm room, 1955.

Alice Irby was a member of Woman’s College Phi Beta Kappa chapter.

Students dressed for a school dance, 1954.

Making way for change

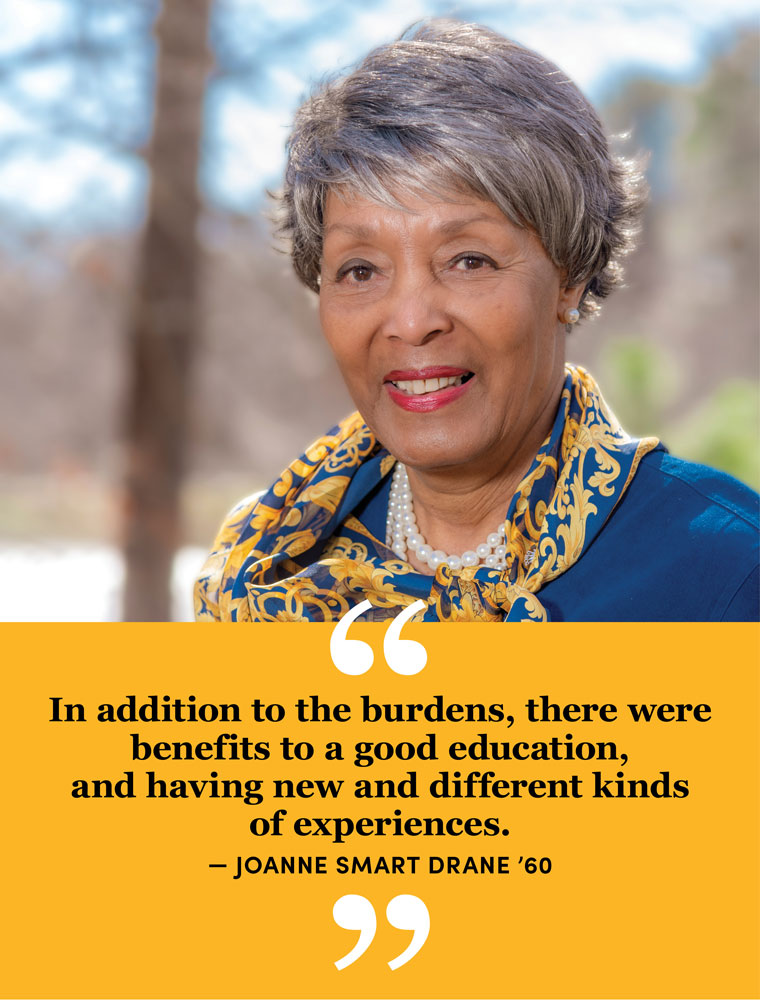

Two years after the Supreme Court’s landmark decision, Woman’s College accepted its first two African American students: JoAnne Smart Drane ’60 and the late Bettye Tillman ’60.

JoAnne was the first in her family to go to college. Growing up in Raleigh, she recalls only one professional – a teacher – living in her neighborhood. She was nervous coming to WC, but determined to get an education.

JoAnne Smart Drane ’60 and Bettye Ann Davis Tillman ’60 (l-r) were the first two African American students at WC

Once on campus, JoAnne and Bettye were given their own wing in Shaw Hall. After settling in their first night, they decided to play it safe, opting against going to get dinner. “We didn’t know what it was going to be like,” said JoAnne. “But the very next day, because we were famished, we said we were going to go out and get breakfast no matter what the situation was.”

When they entered the dining hall the noise level descended. ”You couldn’t hear any conversation at all,”

she recalled.

A little uneasy, they proceeded through the silence. But by the time they grabbed their meals and came back out to the dining hall, the cafeteria chatter had resumed. And their anxiety had somewhat diminished.

As time passed, JoAnne found some of her peers kind, and others outwardly intolerant. Still, she shared her experience with other African American students. After inviting Margaret Patterson Horton ’61 for a weekend visit to the campus, Margaret would enroll as the third African American student at the college.

“In addition to the burdens, there were benefits to a good education, and having new and different kinds of experiences. So we wanted to share those experiences with others,” said JoAnne.

“The College brought in a lot of cultural activities – theater and music and speakers that were very, very important in the overall development of a student.”

Even though she had been her high school’s class president, as well as a cheerleader and basketball player, the uncertainty of how she would be received kept JoAnne from joining social organizations at WC. Still, she found a network of support.

“I think one of the things that was so helpful to the African American students who were at Woman’s College at the time was the fact that the Black community in Greensboro was so supportive and encouraging.”

A few more Black students trickled into WC just after JoAnne. In addition to Margaret, she became friends

with Zelma Amey Holmes ’61 and Claudette Graves Burroughs-White ’61 – who later became a well-known Greensboro City Council member.

They spent weekends with Claudette’s family and attended athletic events together at North Carolina A&T. Long after graduation, they would remain friends, connected, in part, by their shared experience.

Class jackets

The first class jacket appeared in 1927. It was a blue flannel blazer, designed with simple white piping and “N.C.C. – ’29” on the front pocket emblem. After gaining popularity, the jackets began to include students’ initials, placed on or directly above the pocket with their class year.

In the WC era, each class had a set of class colors. Every year, the colors consistently alternated between blue and white, green and white, red and white, and lavender and white. Their jackets corresponded to their class colors — with navy being the preferred blue — and black and charcoal jackets seemingly substituted

for lavender.

Jackets arrived during the fall of the students’ sophomore year, and “Jacket Day” was a highly-anticipated event. These jackets were considered, by many, more significant than a class ring. They distinguished the women as scholars and were worn proudly.

AS THE ’60S NEARED

In August 1958, Ricky Nelson’s “Poor Little Fool” and Bobby Darin’s “Splish, Splash” topped the pop charts. Elvis had been inducted in the Army. The U.S. created NASA, as its “space race” with the Soviet Union sped ahead. On campus, the original McIver Building was in rubble, making way for a modern, new McIver Building.

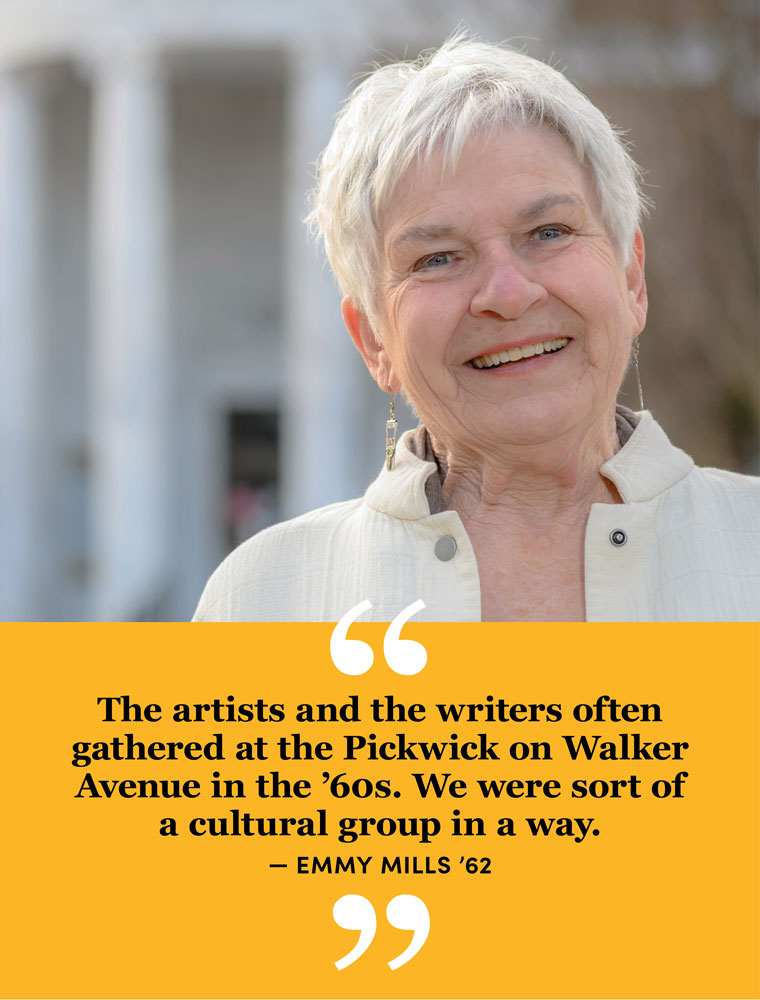

At the same time, Emilie “Emmy” Mills ’62, ’65 MFA was entering her freshman year. She had come to study art, having heard great things of the founder of the art department and the Weatherspoon, Gregory Ivy. Unfortunately for her, Ivy would soon be leaving.

“The department was in a period of transition during most of my undergraduate years,” said Emmy. But the leadership was still top tier. “Several of the professors that were here, had been here for some time. Susan Barksdale, Norma Hardin, and Helen Thrush were the fixtures of the art department and had very good reputations.”

However, according to Emmy, most of the favorite professors of art students were in the Department of English: notably, Randall Jarrell (future Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress), Robert Watson, and Fred Chappell.

“The artists and the writers often gathered at the Pickwick on Walker Avenue in the ’60s. We were sort of a cultural group in a way. In some cases, we were looked at as the interesting people – but then on the other hand I think there were other students who thought we were kind of weird,” Emmy chuckled.

Unifying students was the dress code. Dresses, skirts, and blouses were the standard. No jeans, no slacks, no sleepwear! (Though lots of times girls would roll up their pajama bottoms and put raincoats on to evade the protocol.) Even going across campus in your gym suit was a violation. If you had a class after gym, you had to change clothes.

“As art majors, we didn’t like the dress regulations because we always wanted to wear casual clothes in case clay, paint, or etching acid got on us. But we had to wear smocks,” Emmy explained.

Aside from their fashion, another thing the women of WC had in common was a wealth of academic talent. Dean of the Graduate School J. A. Davis analyzed statistics from other state colleges and scores from the College Board Scholastic Aptitude Test (SATs) for the freshman class in 1959. He found that WC students ranked well above those of any other public college in the state in high school achievement. He also found that they were in the top third of freshmen in the nation, as was true of Chapel Hill and N.C. State.

As a classmate of Emmy’s, Sarah Shoffner ’62, ’64 MS, ’77 PhD describes her experience at WC with an emphasis on “opportunity.” Sarah’s mom took teacher-certification classes at WC, and her great aunt had taught math there when it was known as the Normal College. So she was thrilled to follow their steps.

She was also happy to find encouragement from faculty. As an undergraduate she was asked to fill roles that she wouldn’t have considered on her own.

“The faculty and the administration, particularly in the School of Home Economics, if they got an idea of something you could do or something they wanted you to be involved in, they would ask you,“ she explained.

“My first opportunity in that sense was when I was asked to be president of the WC student member section of the American Home Economics Association … It gave me a chance to see what I could do, but also, I guess they were recognizing something in people that they wanted to nurture.”

“Rush to breakfast, the 8:10 bell too soon,” Pine Needles, 1958.

Her senior year, Sarah was offered a graduate assistantship. Her future position would be teaching home economics classes and supervising a student teacher at the Curry School. To prepare, she was advised to go to summer school and take a supervision course.

“Our school was one of the strongest programs in the nation for Home Economics at that time, so I got to meet a lot of people,” she remembers. “And when I became a faculty member, Naomi Albanese sent me to some of the administrative meetings of the American Home Economics Association and let me participate and represent her sometimes. So I was just given opportunities to get to know people, learn, and branch out,” she said.

“My whole career was having opportunities available that I could latch on to.”

PASSING THE TORCH

Sarah began teaching at UNCG in 1964, and she served in various research and administrative roles in the School of Human Environmental Sciences. She developed internship opportunities for hundreds of students who were in the child development and family studies major but didn’t plan to teach preschool or K-6. She was honored with the NC Home Economist Award, the state’s highest award in the profession.

After earning her MFA at the University, Emmy returned again to work in Jackson Library. It was then that she was encouraged by the library director to go to library school. She completed that degree at the University of Illinois and then returned as UNCG’s first director of the Special Collections – now called the Martha Blakeney Hodges Special Collections and University Archives. Under her guidance, collection development plans were written for the University’s rare book collections, manuscript collections, and university archives – contributing greatly to the needs of the academic community, scholars, and students.

An invitation from the UNCG Neo-Black Society would bring JoAnne back to the University 20 years after earning her degree. “Once I got back and saw … that the University had grown in its acceptance and involvement of students – particularly African American students – and that there were also African American faculty, it just opened my eyes to the kinds of things that had developed in that period of time since I had left.”

With a newfound connection, JoAnne became a regular speaker for campus organizations, sharing her experience as a pioneer of diversity and issuing words of encouragement to students over the years. She would also serve as first vice president of the Alumni Association and on several boards of the University. Outside of the University, JoAnne dedicated her life to the education sphere, leading in several director roles throughout her career and retiring as a consultant in teacher education.

Five years after graduating from WC, Alice Irby returned as the College’s first director of admissions. Charlie Phillips and Mereb Mossman had brought her back to the College to assist with recruitment, and Mossman gave her the new leading role. She touched the lives of many students – bringing a perspective of WC alumna to the role. “We made it a special mission to recruit girls from every county in the state, and that meant a lot of first-generation, rural students, as well as students from various ethnic backgrounds,” said Alice.

After working at the College, Alice would go on to work as the vice president of student services at Rutgers University, a role that awarded her recognition from The New York Times as “the highest‐ranking woman in the administration of a major American university.”

Alice, JoAnne, Emmy, and Sarah each provide a unique perspective of someone who returned to their campus to make an indelible mark on the institution and on its students.

They also represent a true part of WC’s legacy: a place where the marginalized were the majority; free thought was expected; and faculty were often like family, making it their personal responsibility to guide students to success.

Like the thousands of “WCers,” they are proud of the academic excellence of their college, confident of their mark on the state at a time when women were expected to take a back seat. And like so many from their era, they have remained close friends of the University, passing down their wisdom and lessons learned, shaping UNCG into what it is today.

WC Tribute

Designed in collaboration with landscape artist James Dinh and sculptor Michael Stutz, the Woman’s College Tribute will be a circular communal space in front of the Mary Frances Stone Building. Three-tiered brick walls will surround a central statue. These walls will hold flower planters as well as image panels composed of text and photographs from WC-era yearbooks.

The central sculpture, affectionately named “Astera,” will be the head of a woman made of woven bronze. Simultaneously a modern interpretation of Minerva and the embodiment of the aspirations and spirits of the women who passed through WC’s halls, Astera will gaze across the quad. Students, staff, faculty, alumni, and visitors will be able to stand behind her and, through her eyes, see the campus that has changed thousands of lives.

“The Woman’s College Tribute is a permanent reminder that for some 30 years there was a College that taught women there was an alternative to the traditional role that was expected of them,” said Agnes Johnson Price ’62, ’71 MEd, a member of the WC Tribute steering committee. She, herself, went on to teach in the Accounting department at UNCG from 1981 to 1997, seeing firsthand the strong WC legacy of excellence.

“It instilled independence, free thinking, leadership, and the necessity of overcoming challenges in family, in business, and in life. It introduced a more practical and realistic, but still elegant, image for women in society. Furthering its major contributions, Woman’s College is the foundation of the current UNCG.”

Learn More about the WC Tribute

Photo Gallery

[widgetkit id=”11″]