Our History Too

AS UNCG ARCHIVES MAKE CLEAR, THE LGBTQ+ COMMUNITY HAS BEEN HERE ALL ALONG.

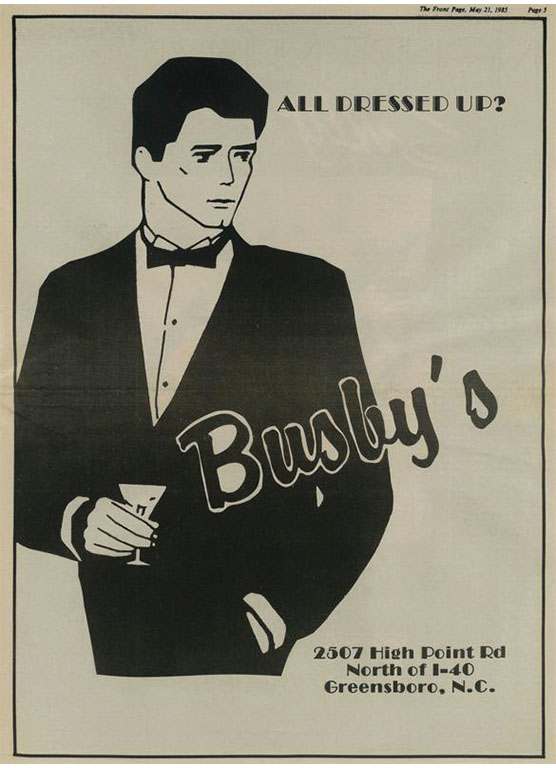

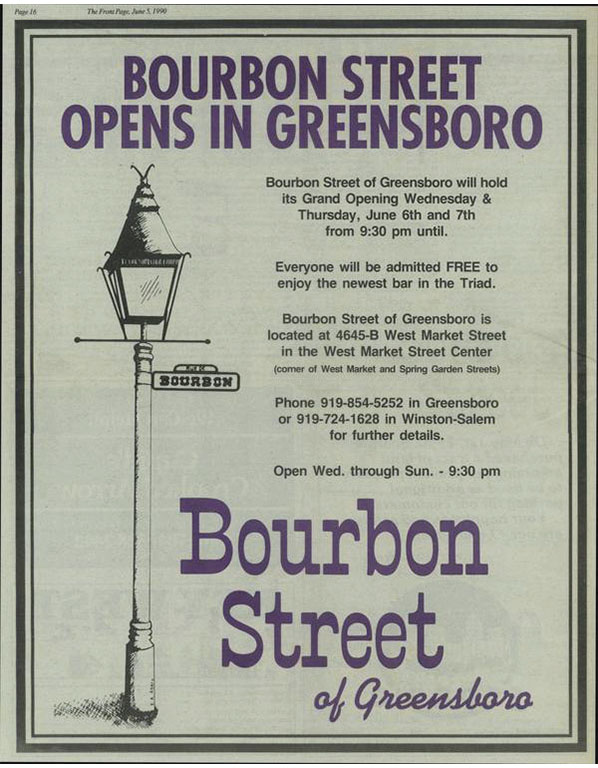

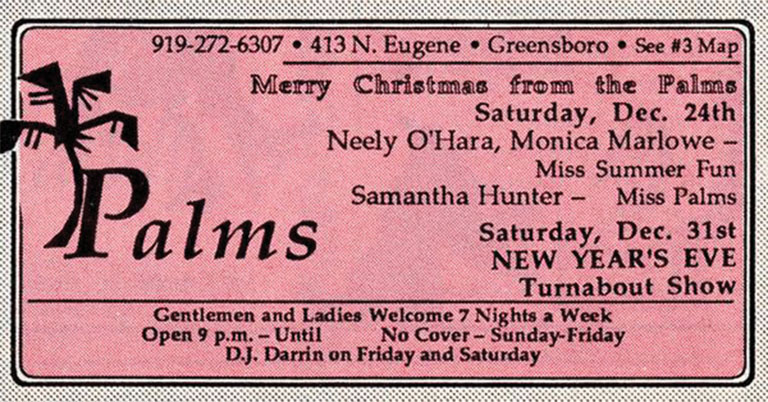

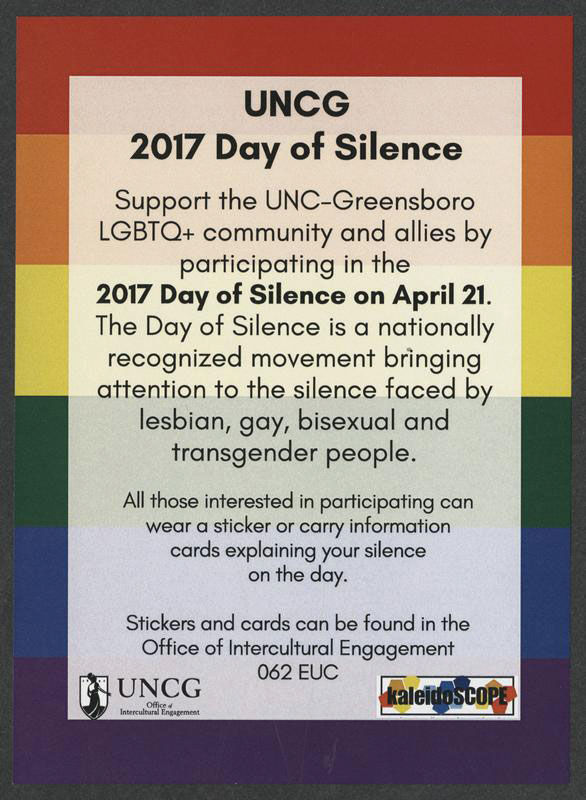

IN THE UNIVERSITY’S ARCHIVES, you can find memorabilia from Coming Out Day events, fliers from Greensboro’s gay bars, and scrapbooks lovingly kept by students simply documenting their lives.

These items are donated by LGBTQ+ community members, then digitized. The collection also includes recorded interviews that tell a story too often kept hidden.

UNCG librarians Stacey Krim and David Gwynn ’91 archive and share this growing collection, PRIDE! of the Community. Initially funded by a National Endowment for the Humanities Common Heritage Grant, it documents not only UNCG’s LGBTQ+ history but also that of the Triad region.

“Because they were a historically persecuted group, LGBTQ+ people found it was dangerous to leave a paper trail,” says Krim. They needed to remain invisible and could not rely on mainstream institutions.

Until recently, it was not safe for gays, lesbians, or other queer individuals to “live and love” publicly. Today, members of the community talk about visibility.

“Visibility inspires people to break some of those stereotypes and barriers that they may have grown up with,” explains Brad Johnson ’09 PhD, current professor and former staff member in Residence Life. It also means seeing other LGBTQ+ people in daily life.

UNCG has a longstanding reputation as a safe place for queer students, but the institutional support that LGBTQ+ people see now has not always been there.

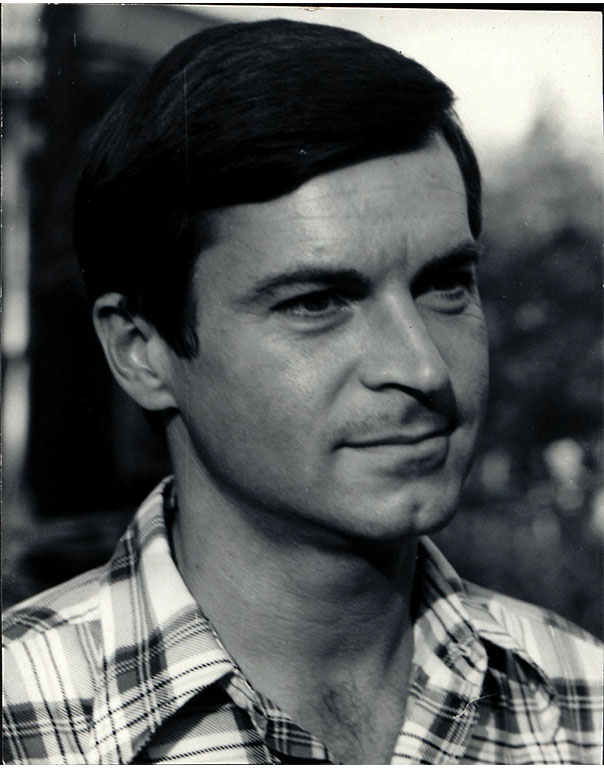

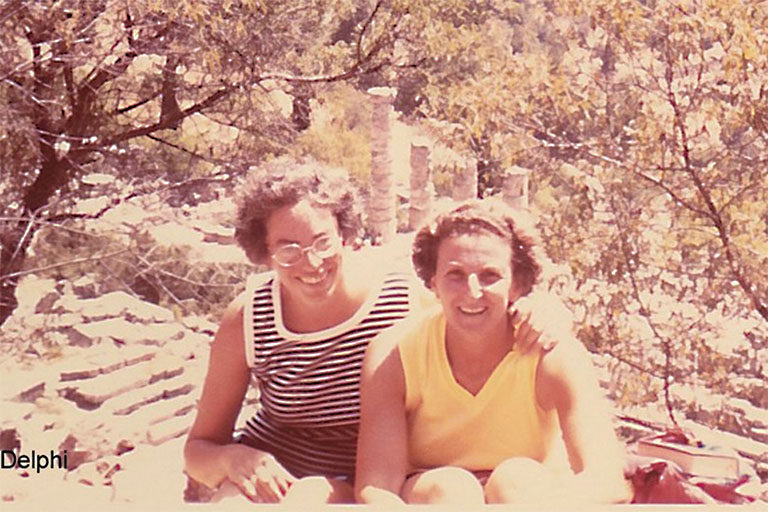

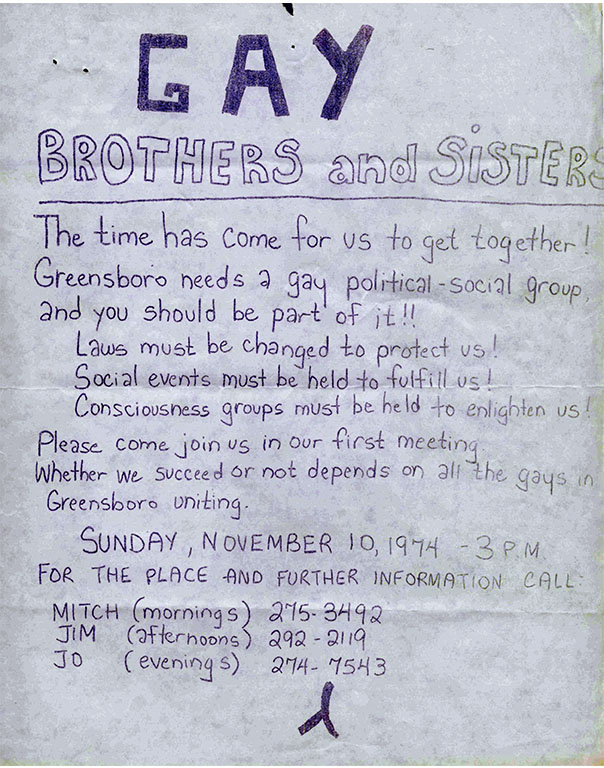

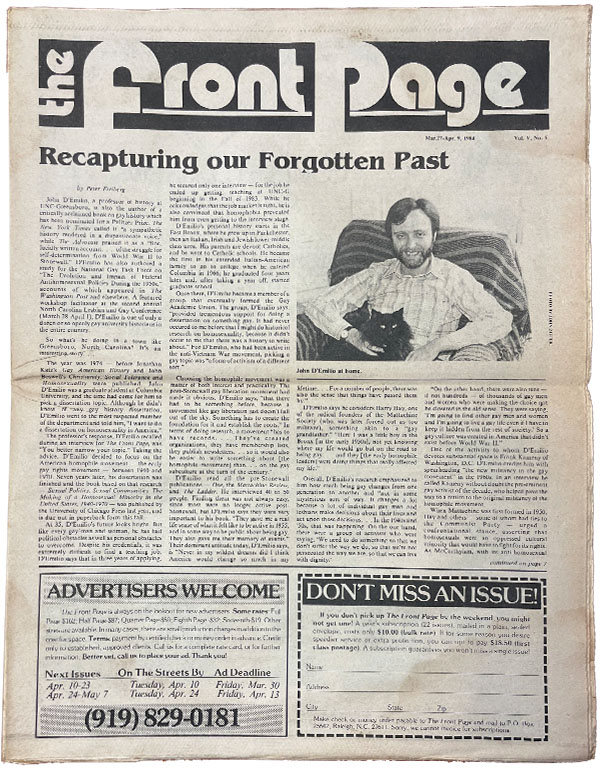

Left to right: Dr. Thomas Fitzgerald taught the first course about LGTBQ+ issues in the UNC System; Lennie Gerber and former professor Dr. Pearl Berlin took lead roles in the fight for marriage equality; A flier from 1974 shows an early attempt to create an LGBTQ+ organization; Photo from an event organized by the Guilford Alliance for Gay and Lesbian Equality (GAGLE), 1988; John D’Emilio on The Front Page, an independent newspaper, mid 1980s.

Over the past decades, these students and faculty had to create their own networks, educate others about their existence, and fight for their basic human rights. Even now, UNCG is not perfect.

But it has come a long way.

ONE WC ALUMNA who came out as a lesbian in the 1970s reported that issues like sexuality were not common topics of discussion when she was a student in the mid 1950s.

There were also real threats to the safety of LGBTQ+ people from other citizens and the law itself.

Krim presents information about Greensboro’s Gay Purge as part of her crash course in UNCG’s queer history.

Drawing inspiration from McCarthy-era witch hunts and the mid-century antihomosexuality “Lavender Scare,” Greensboro police arrested 32 men in 1956-57 for “crimes against nature.” For much of the century, those who were not heterosexual knew they could see their livelihoods, physical safety, and freedom slip away with a simple accusation.

Courage to be vulnerable

ETHAN HUTCHINSON ’06, ’10 MED comes by his Spartan pride honestly. His mother is an alumna and his parents were married in the Alumni House. At Pride Prom in the late 2000s, he wore a blue and gold plaid blazer. “I wanted to look like UNCG.”

Those years were times of serious change for him.

“I could not have picked a better undergraduate institution to be a lesbian-identified person. Then, I also could not have picked a better institution to transition from female to male as a graduate student,” he says.

On campus, increased dialogue was met with an angry protest in 1979. At a planned lecture and discussion intended to diffuse tension, protestors wore masks, shot fireworks in the air, and carried derogatory signs. Reported sources of tension were the new Gay Student Union and the presence of an openly gay student living in Strong Dormitory.

But the most visible tragedy for the LGBTQ+ community on campus happened when a student took his own life very publicly. The news and editorials shone a bright spotlight – and brought about more understanding. That story shows how even the dark chapters of history offer a hope of change.

WHAT DOES LGBTQ+ MEAN? It is an “umbrella” term used to include all people who identify themselves as being outside of a “traditional” cisgendered and heterosexual identity.

The main letters of this “alphabet” stand for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning. The “plus” stands for other identities that are not cisgendered and heterosexual.

Though this was not always the case, today “queer” is also used as an “umbrella” term. UNCG’s Office of Intercultural Engagement prefers the term LGBTQ+.

The truth is, each individual is unique.

From Newsprint to Novels

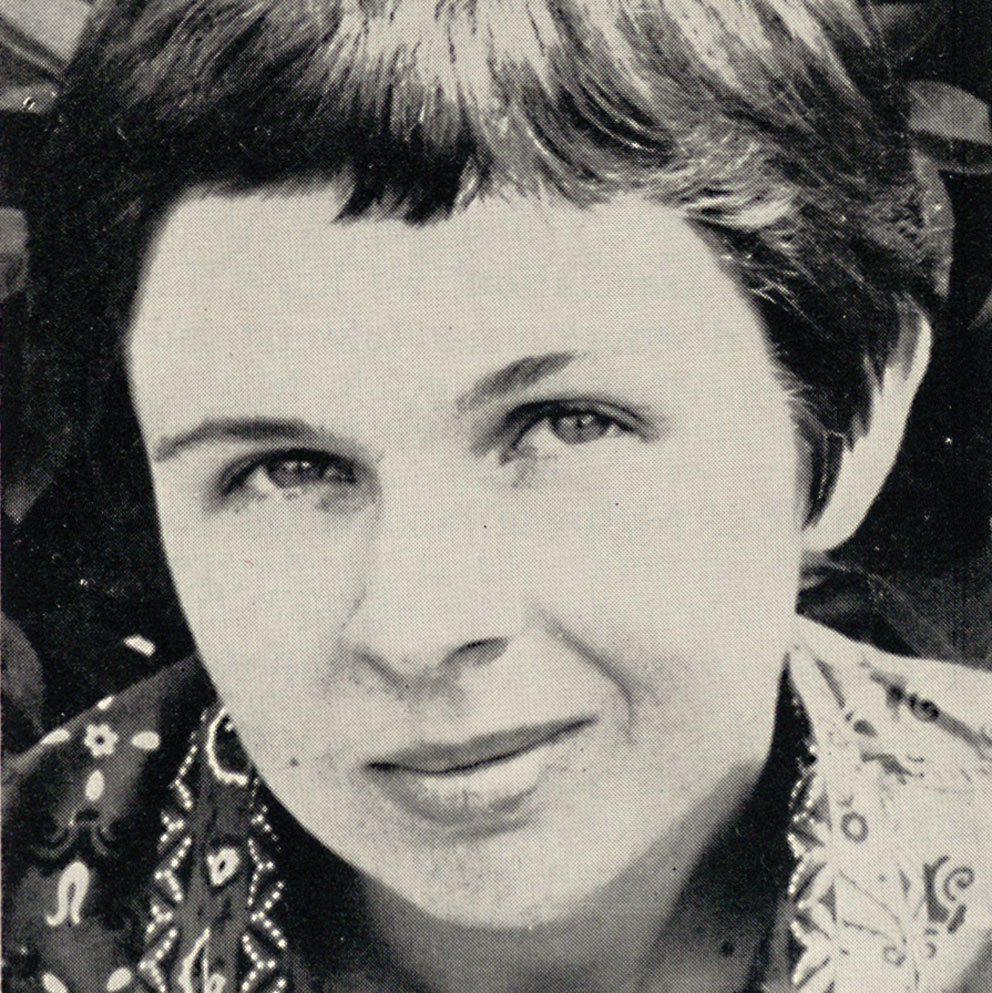

BERTHA HARRIS ’59 BA, ’69 MFA was a lesbian feminist writer whose work is stylistically rich, playful, and steeped in both literary history and the Women’s Movement of the 1960s and ’70s.

As an undergraduate at Woman’s College, she wrote for The Carolinian, responding to campus issues with edgy wit.

She was one of the campus intellectuals and freethinkers known as the “Black Stocking Girls.”

“You can’t lump everybody together,” says Johnson. “Our identities have different facets, like a diamond. We know that our perception of who we are as human beings and individuals has grown and expanded.”

The University’s LGBTQ+ history has moved mostly in step with that of Greensboro itself, says Krim. “What makes us different is that, for a Southern city in the ‘Bible Belt,’ we seemed to have a larger and more visible LGBTQ+ community.”

Greensboro has historically been able to support more LGBTQ+ nightlife and social spaces than other comparable cities. This hints at a vibrant community, Gwynn of UNCG Archives notes.

John D’Emilio, the former UNCG professor and celebrated historian, arrived from New York City in the late 1980s. In a 2018 interview, he said he wanted to know there was gay nightlife in Greensboro before moving “because that symbolized to me that there must be a community.”

Local organizations like Guilford Green Foundation & LGBTQ Center continue to show the diversity and strength of Greensboro’s gay communities.

FOR MOST OF AMERICAN HISTORY, gay and lesbian identities have been, if not persecuted, kept hidden “in the closet.”

In the 2010s, one couple with UNCG connections became notable in the fight for marriage equality. Pearl Berlin, a former head of the Department of Kinesiology, and her spouse, Lennie Gerber, were lead plaintiffs in a case against the state of North Carolina. They wanted the state to recognize their right to marry.

An eventual victory came with the federal Obergefell v. Hodges case in the United States Supreme Court. For LGBTQ+ couples, this decision was a long time coming.

Lennie Gerber recalled that in the 1960s, many “open secrets” were not discussed. Worse, there was outright discrimination. When Pearl Berlin was hired by UNCG in 1971, Gerber also tried to get a teaching position.

According to Gerber, faculty members told her that UNCG “will not hire you because you (and Berlin) are too open.”

The Accidental Trailblazer

MICHAEL TUSO ’11 was the first in his family to go to college. Although it was the last thing on his mind, he was also the first openly gay student body president at UNCG.

“I never thought about it,” he says. “I was thinking, ‘Let’s get to work, let’s roll up our sleeves.’ That was the kind of naivete I had.”

After he was elected, newspapers like Qnotes Carolinas, which publishes LGBTQ+ news and stories, started calling. Tuso didn’t mind the coverage. Most family and friends, including his mother, knew who he was already.

Dr. Kathy Williams ’74, who graduated from UNCG and then returned in the late 1980s as a professor, had a different experience. She remembers fellow faculty and administrators accepting her warmly.

When Williams and her partner finally got married after the Supreme Court decision, her dean attended the wedding.

“We were actually at a hockey game when the decision was reported,” she remembers. “Now, my spouse and I have been together for 25-plus years and have been married for six and a half.”

EVEN THOUGH RELATED STUDENT CLUBS and organizations began to exist on campus in the 1970s and ’80s, LGBTQ+ life was still on the margins.

And members of gay and lesbian communities had to advocate for themselves.

The three goals of the Gay Student Union, a UNCG student group created in fall 1979, were: “To educate the public about the legal, social, and personal aspects of homosexuality,” “To provide a support system for those in the organization,” and “To represent the homosexual portion of the student body in matters relevant to homosexual students.”

A Gay Student Association pamphlet from 1982 reads like a guide to myths about LGBTQ+ people. It answers questions like, “Are all gay people alike?” and “Can a person be gay and religious too?”

D’Emilio believed that it would take grassroots faculty and staff organizations to see a more inclusive workplace. In fact, it was three students who initiated the process that would culminate in the faculty handbook’s 1996 nondiscrimination clause.

After the UNCG Student Senate passed a nondiscrimination clause, three students, Alesha Daughtrey ’97, Jessica Stine ’97, and Mandy Vetter, asked the Faculty Senate to approve a similar statement.

Kathy Williams remembers a fiery debate. “One faculty member stood up and said, ‘Why does this group need to be privileged?’”

But to Williams, freedom from discrimination is not a special right. “So, a gay person wants to get married or not have to worry about being beaten up coming out of a bar – I mean, what is special about that? Those are human rights.”

No Labels, Welcoming All

HOW DOES A GROUP CALLED NO LABELS describe its mission? “To provide a safe space for queer people of color, allies, and advocates through volunteerism, advocacy, educational programming, collaboration, and inclusion.”

“No Labels was created in 2017 by an African American queer student because they felt there wasn’t a place for queer people of color, specifically African American voices, to be heard,” explains Isaiah King ’23, the club’s current president.

After two failed attempts to adopt the clause, Dr. Jim Carmichael, then an associate professor in the Department of Library and Information Studies, brought a revision.

“I urge the senate to pass this not only for the self-interest of a largely invisible minority, but so that this University may go on record as a leader in sensitivity to human rights.”

Joy Brown, an undergraduate in the Department of Social Work, presented a 68-page petition with 1,045 signatures of UNCG faculty, staff, and students who supported the resolution. It was approved.

To this day, many fear that legal protection for members of the queer community is not reliable.

“I don’t feel like this at UNCG, but there are other environments where if I were to identify as gay back in the day, that would easily have been grounds for dismissal and I would have no recourse at all,” says Johnson.

ALMOST THIRTY YEARS AFTER that nondiscrimination statement, LGBTQ+ people are safer and more visible than before.

Student groups like No Labels will offer events for Pride Month. One thing they want to talk about is the most visible tragedy in UNCG’s LGBTQ+ history, the suicide of Kenneth Crump.

The 21-year-old dance major, French horn player, and resident of Strong Dormitory broke through a ninth-floor window in Jackson Library on Nov. 22, 1982. He jumped to his death.

“I think it’s important to know history,” says Isaiah King ’23, the president of No Labels. “We should know about things like someone committing suicide or protests outside of the first LGBTQ+ lecture so they don’t happen again.”

Professor Jay Poole ’84, ’99 MSW, ’09 PhD remembers vividly that dreadful night in 1982. He was returning to campus with friends. They passed the library tower, saw the fire trucks, and, later, heard the rumors.

“I heard rumors that Kenneth Crump had been really harassed. I think that probably kept me very concealed. It certainly didn’t bode well for being open on campus,” he said.

Some positive actions were taken after the tragedy. As with the nondiscrimination clause, students led the way. The Student Government Senate requested additional state funds to support UNCG’s Counseling Center after the tragedy.

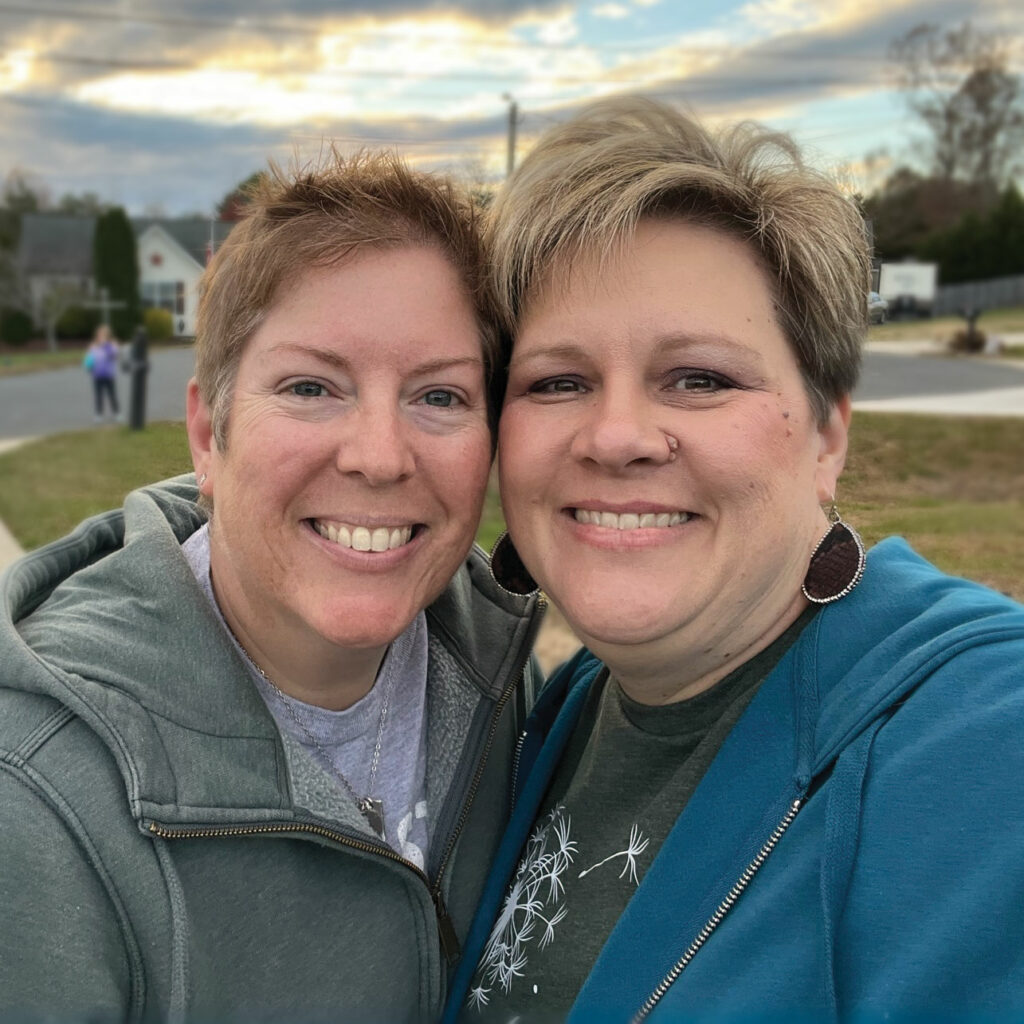

Colie Hayes ’00 and Heather Whitlock ’00 met during their junior year of nursing school. “We were in maternity clinical and became instant friends,” Heather said. The two kept in touch over the summer, writing letters back and forth, and took several group trips together during the fall of their senior year. “I couldn’t figure out why it was that I just had to be around this woman,” Heather said. On a spur-of-the-moment beach trip in October 1999, they shared their feelings for each other and have been a couple ever since. “Twenty-three years later, we are happy as ever,” Heather said in a recent “Spartan Sweethearts” web post. They have two children and married in 2016.

Members of the campus community like Poole, whose personal journey is closely connected to UNCG, believe UNCG offers a safe environment for all of today’s students.

“UNCG helped me with my whole outlook on the world and my perspective on the world, which, of course, is what education is all about: transformation,” he says.

With today’s students and elders educating others about UNCG’s queer history, the campus may continue to heal and grow.

“We were founded by a revolutionary, Charles Duncan McIver, who founded the institution because he believed in the education of women, which was not popular at that time,” says Johnson. “I think that there’s a good history of being a little radical in some respects: making sure that everybody is identified, affirmed, and recognized.”

BY MERCER BUFTER ’11 MA • PHOTOGRAPHY BY SEAN NORONA ’12

Behind the scenes

Behind the scenes of “Our history too,” a feature about UNCG’s LGBTQ+ students and alumni.

We wanted to highlight UNCG’s supportive environment for a diverse array of students. The team used College Avenue, the help of the Theatre Department’s Amy Holroyd, and some creative photography to show the connection between UNCG’s past and present. Student models Ruthanne Baiardo and Jaye Ivey even supplied some of the vintage clothes!